Home

page | Articles index | Search for more information

More Interviews

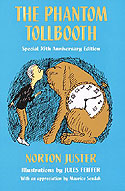

An Interview with Norton Juster, Author of The Phantom Tollbooth

Books by Norton Juster discussed in this article:New by Norton Juster:

The Hello, Goodbye Window was named the 2006 Caldecott Medal winner. Click the links above to go to Amazon for information about the books, or to buy them. Purchase of these books helps to fund this site: find out more. |

There is only one universally acknowledged fact which is undeniably, indisputably, unequivocally, and incontestably true. This fact, of which there is not the slightest doubt, is that the entire world is divided into two distinct halves. To qualify for membership on either side of this great divide one must either be a have or a haven't -- have or haven't read The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster, that is.

If you've never even heard of the book, then "Shh, 'cause it goes without saying," we know which group you belong to. The Phantom Tollbooth, as we haves have always known, is the quintessential book for children of all ages, and the language lover's delight for the child in every adult.

Being a literary journalist obviously has its perks. One of them was the privilege and honor I had recently of interviewing Mr. Juster.

![]()

RoseEtta Stone: Hoping praise doesn't embarrass you, I wonder if you even had the vaguest idea forty years ago that The Phantom Tollbooth would be lauded as a "masterpiece," and still be as popular today as when it was first written?

NORTON JUSTER: Well, I really didn't. In fact, it was interesting that not long ago I did a session with a school in which I spoke to various classes. I do a number of these a year. And one of the questions that came up from one of the kids was, "Did you know that this book would be around 40 years after you wrote it?" And I said to him in a kind of facetious way, "I didn't know it was going to be around 40 minutes after I wrote it." And that's really true. It didn't occur to me. And one always likes the idea that what you do is going to be liked by someone, or it's going to be enjoyed, or it's going to be successful. But really, I had no idea.

RES: What, exactly, do you think it is that so enchants kids about the book? And at what age do they really begin to comprehend and appreciate the puns, word play, double entendres, satire, clever wit and humor, the relationship between numbers and letters, and all else the book has to offer?

JUSTER: Let's start with the first one. You know it's interesting, when I wrote it, it was very personal to me and it really dealt with a lot of the things that I recall -- not so much events as feelings when I was a kid. Having to learn things that I didn't want to learn. Finding myself with a large piece of the time that I didn't know what to do with -- in other words, being bored. All those things. And, when I finished [writing] the book, one of the things I thought about was: I wonder if anybody's going to connect with it. And I think what kids do -- it's a fairly universal kind of thing - I think the general sense of the book - the feeling of it is something most kids experience one way or another. They're at times disconnected, or they don't know what to do with themselves. They don't know why anything is happening. All the things that they're learning don't connect to other things. One of the things that happens in your life is you start out learning a million facts and none of them connect to any other facts. As you get older you gradually realize that something you learned over here connects to something you experienced over there. And you start drawing sort of mental lines, and after a while, like when you get to my age, there's almost nothing that you learned that doesn't connect with 80,000 other things. So it all has some kind of a meaning and context to it, and I think kids slowly begin to feel that too.

RES: I remember Milo, The Phantom Tollbooth's protagonist, beginning to understand, as he traveled onward from one adventure to another, the connectedness between things he had learned in school.

JUSTER: Well, I think that all kids do. I used to read the encyclopedia when I was a kid. We had a big set of them at home and I just read it for fun. And I had this most fantastic assortment of totally unrelated and irrelevant facts at my fingertips with which I used to terrorize teachers. Or if not terrorize them, at least make things very uncomfortable, because I would be throwing stuff in that I didn't know where it belonged or anything. And after a while you realize that things start to connect. And that gets very exciting. And, that, I think is important.

But I think kids like the fun of the book and they like the story. Some books are difficult, and I think with some kids it's not the difficulty as much as boredom, really -- if they don't like what they're reading. And this [The Phantom Tollbooth] has enough of an adventure going on, so they like that part of it. The characters I think are kind of colorful enough so they can relate to those. And I think they relate to Milo as a kid who has some of the same problems -- well, "problem" is probably the wrong word -- craziness, perhaps, that they have.

The other part of your question, at what age do they get it? They get it at different ages. The interesting thing is, I have had a number of these things where I'll get a letter from say a kid whose 9-years-old, and he'll talk to me about the story and mention some of his favorite parts, or whatever. And then five or six years later I'll get a letter that says, "I wrote you when I was 9. I reread the book." And they'll talk to me about a whole different book, normally. But now they've got a lot more of the words right. A lot more of the fun kind of crazy references -- things that go on in there. But I've gotten a few letters where someone in college writes to me. And it's very exciting when that happens. But there's no way of telling, I don't think. Some kids are very attuned to word play and puns and things like that, so they get a lot of it early on. Other kids don't, and they just go with the story. And that's fine too. There is no one way you should ever be able to read anything.

RES: That's interesting. As one's linguistic and vocabulary skills become more sophisticated the story takes on increasingly complex levels of meaning. The story hasn't changed. It's the child or adult who's matured.

JUSTER: Just as a little example: My wife and I were over in England, on a little trip. That you know. And I was interviewed by a childrens' magazine called "Carousel," put out in Yorkshire. And we were chatting and he said, "You know what my favorite part of the book is?" And I said, "What?" And he said, "Well, this one little scene where they're all sitting in this little wagon. And Milo says, 'Shh, be very quiet cause it goes without saying." Now that's something I'd be willing to bet that probably 90 out of a hundred kids 8, or 9, or 10-years-old are not going to get. But it doesn't matter at all cause it gets in the way of the story. But it was something to him, and he had only read it as an adult, you see. So that is kind of nice, when that happens. You realize again, quite accidentally, I think, that there are things in there that appeal to different people at different times in their life.

RES: Since the medium (your book) itself is the message -- not a lesson you moralistically preached at kids, like some writers do, is there an unstated "message" in the story? And do kids, in your opinion, "get" it?

JUSTER: I had no message and I have no idea what specific things kids will get from the book. I think it comes in all different ways -- special ways. There are things I don't think I put in there on purpose, but it's there. It's all about looking at things in a new way. There's a wonderful old "Peanuts" cartoon that sort of embodies this. When I was in school it always used to amaze me when you would read a story or poem, or something. Then the teacher would ask a whole lot of questions about it. And then at the end she would tell you all the things in the book that you had no idea were there. All these conflict things. Especially in poetry, which I like to read. Well, Charlie Brown and Lucy were talking about poetry. And in the next little box in the comic strip, Charlie Brown asks, "But how do you know what it means?" In the last box she says, "Someone tells you." And it's absolutely perfect.

And oddly and tragically enough, I think that kind of thing carries into adulthood with a lot of people. They simply will not make up their own minds about what they're reading or what they're doing. They're almost always waiting to be told what it is that they have read. Or what it means. Or how important it is. Or whatever.

RES: Another question: Has The Phantom Tollbooth's puns and word play, etc., prevented it from being translated into other languages?

JUSTER: It's been translated into a lot of languages. I have no idea what they're like. That's the problem. But there must be a dozen different languages that it's in at the moment: Swedish, Dutch, Italian, Polish. Now a French edition, or there will be. There's one in Japanese. There are three Spanish editions -- one in Spain, one in South America, one's a US Spanish edition. There are two Portuguese. And there is a Catalan edition for the many people who speak Catalan. I don't know how many there are.RES: Really! Can such idiomatic words and phrases be translated into other languages?

JUSTER: I have the same question. It seems to me that they would translate most easily in a Germanic language which is most akin to English structure. But even then I don't know. I couldn't read it in Swedish and Dutch. In fact, when the Japanese were doing it they sent me a big package with the galleys and all the stuff and said, "Would I please check through all this and see if it's okay?" And, of course, I opened it up and there was just a mass of paper that I couldn't begin to deal with.

RES: One of your other wonderful books, The Dot and The Line was adopted into an Academy Award-winning animated film. Wouldn't The Phantom Tollbooth also lend itself perfectly to animation?

JUSTER: It was done as a full-length animated feature film by MGM. With live scenes. Live beginning and end. And when you go through the tollbooth is when it turned into animation. It was a film I never liked. I don't think they did a good job on it. It's been around for a long time. It was well reviewed, which also made me angry. And for some reason, I don't know why, they never put it into general release. But it played a lot and it still does, on television.

RES: I don't know that I've ever heard, saw, or read about its being on TV.

JUSTER: It's drivel. So don't worry about it. I don't own the rights anymore, but the conglomerate that owns it, MGM, Turner, Time Warner, AOL, they're now very seriously considering remaking the movie as an all-live action film. That's the way I'd prefer it. Whether it happens or not I don't know. I've had enough dealings with the crazy movie world to know that a vast majority of things never happen as they say. And if they do happen, they happen at a glacially slow pace. What I try to do is put it out of my mind. If it does go ahead, I hope I will have some function in it because I'd like to do it in a way that I think it should be done.

RES: Is it also true that you collaborated on a libretto for an opera based on The Phantom Tollbooth which premiered in '95, and was expected to be performed in schools or opera houses nation-wide? Was it? And is it available today on something like CD's?

JUSTER: I have to go all the way back to the beginning. I got a phone call from a group called Opera Delaware, in Wilmington, Delaware. They are a small opera company. And for their 50th season they asked if I'd be interested in adopting it as a treatment for an opera. Well, I was intrigued and talked to a wonderfully talented friend of mine, who was also interested, who talked to a 95-year-old friend of his who worked on "Fiddler On The Roof" and "Figarello," and a whole lot of other great Broadway shows. They worked on the libretto with me. We had a ball doing it. And we had a production in Arlington, Virginia and Northhampton, Massachusetts. For a while there haven't been any productions. But we're now working on two versions of it -- the full-length version, and a shorter school version. And we're very hopeful that the productions will be starting in a year or so.

RES: Getting back to a subject you broached earlier in our discussion, mail you've received over the years from readers, whom have you heard from most -- kids or parents?

JUSTER: Oh, mostly kids.

RES: What, generally -- if such a generalization can be made -- do they write?

JUSTER: You can't generalize. Sometimes you'll get oh, absolutely wonderful letters. Sometimes you'll get a letter that's just hilarious, like "Dear Mr. Juster: I'm writing because I read you are still alive." Or, "I'm writing because my teacher told us we had to." Or, "Dear Mr. Juster: I found your book boring." I've had a few of those. When you get individual letters from kids they're often very nice. When you get batch letters sometimes they're a bit of a formula, you know -- this is what you do in the first paragraph, then the second paragraph you tell him what your favorite part is. And so on.

And sometimes I have relationships with oh, I'd say at least 6 or 8 teachers now in various schools. But the ones that I find the most interesting and enjoyable -- one from Texas. And one from a town in Southern California, where every single year I'll get a package of letters and pictures and drawings -- all kinds of things because the teacher uses it every year in her class. And those are usually wonderful, spontaneous, and always great to get. So I reply to them all. That's great fun to do. But I have to be very careful. You can't repeat yourself, because the teacher says, "Oh, I put your letters up on the wall. They're all there from the last 12 years." I've got boxes and boxes of letters and I answer them all.

RES: That's quite a chore.

JUSTER: It is. But it's important because I can remember writing letters. Not getting replies. Not nice for kids. When you write you should get a reply.

RES: Who, in your opinion, gets a greater kick out of The Phantom Tollbooth--kids or parents?

JUSTER: Well, probably more kids read it than parents. I talk a lot to parents because they're quite often parents who have read it as kids. On a number of signings that I've done I'll get people who'll come up with an absolutely tattered copy which they say they've had for the last thirty years, or so. I think a lot of kids read it and it becomes part of their lives. And they will pass it on to their kids, and that whole sequence is also very satisfying.

![]()

"I didn't even know who it was for. I mean, I vaguely knew it was a childrens' book. But when I brought it to the publisher and they mentioned, "Well, what age group do you think this is appropriate for?" I really had no idea. I was a babe in the woods. I didn't know anything about childrens' books. Or rules for writing them. Or how they sold."

![]()

RES: Moving on more specifically to your experiences as a writer, if your publishers had had their way and edited the book as they thought it should be written, do you think it would have become the beloved classic that it's been for the past 40 years, and still is? I'm assuming, of course, that they would have wanted you to follow the "prevailing wisdom" of the time you mentioned in your interview on Salon.

JUSTER: I'll tell you something. The publisher did not ask to change or reedit it, or anything. I worked with a single marvelous editor at Random House. He had a million suggestions and we talked them all over. None of them really addressed the issue of simplifying or "dumbing down" the book. When I wrote the book I really didn't write it with any sense of mission. I wrote it for my own enjoyment. The book in no way was written to any sense of what it was that children needed or liked. It was really written as most, I think, books are by writers -- for themselves. There was something that just had to be written, in a way that it had to be written. If you know what I mean.

I didn't even know who it was for. I mean, I vaguely knew it was a childrens' book. But when I brought it to the publisher and they mentioned, "Well, what age group do you think this is appropriate for?" I really had no idea. I was a babe in the woods. I didn't know anything about childrens' books. Or rules for writing them. Or how they sold. Or what the situation was in the childrens' book world. So I had really no expectations other than the vague one of, "Gee, I hope someone likes it."

RES: Your interview with Laura Miller of Salon contained advice based on your own experience, and a number of useful suggestions for writers, such as, and I'm paraphrasing now, the book that turns out to be successful should be the book that you weren't supposed to write. Would you explain that please?

JUSTER: (With a big laugh), I find -- this is a very personal thing. But I find the best things I do, I do when I'm trying to avoid doing something else I'm supposed to be doing. You know, you're working on something. You get bugged, or you lose your enthusiasm or something. So you turn to something else with an absolute vengeance. You throw every bit of your attention into it because you're trying to avoid in any way getting back to that other thing. So that was a kind of facetious remark I made to her.

RES: You also spoke, in that interview, about initially submitting a grant to write a childrens' book about urban aesthetics.

JUSTER: Oh yes. That's the book that I wanted not to do. That's why I wrote The Phantom Tollbooth.

RES: I think I speak on behalf of the entire planet in saying that we're so glad you changed your mind! I wondered though, and maybe other writers would too, whether or not the grant you applied for came through? And what happens in the event that one gets a grant for a specific purpose, then winds up using it for another purpose entirely? In this case for writing a different book?

JUSTER: Well that was on my mind, of course. So I sent a copy of The Phantom Tollbooth to the Ford Foundation, so they'd understand. And explained to them that I had not done the book that they had given me the grant for. I did this, and in all truthfulness, a number of things that were in The Phantom Tollbooth were generating some things that I'd been thinking about because of my work on the grant book.

One was the Cities Of Illusion and Reality -- the cities disappear but people don't notice it. There were several things that came directly from things that I was either thinking about, or had done research about for the book on cities. Anyway, I explained all this and I never heard from them. But at that point I had my entire grant. So I had some money and the money did provide the time for me to do the book I wanted to write. So I hope they're not upset.

RES: Never having applied for a grant, I had no idea how it all worked.

JUSTER: Oh, neither did I. I was terrified! My sense is that when you give a grant -- I mean, I have no experience so I'm now talking off the top of my head. But it seems to me, I think you have to be prepared for the idea that something will be generated that may not be exactly what you anticipated. But that's fine because the whole idea of giving someone a piece of time to pursue something, is that that pursuit might lead to something unanticipated. And that's great. So I don't think you can be that product oriented. I mean, there's a difference between taking a grant and squandering it or taking it fraudulently and not doing it. That would legitimately upset someone. But this is a different situation. It's one of the things that's very nice about the McArthur genius grant, which I have never gotten (Juster chuckles), I'm afraid. And I don't anticipate getting it. But one of the things I've always admired about that setup is they give the money and say, "Okay, this is to give you the time to pursue what you want."

RES: Tell us, if you will, how you managed to incorporate this language lover's delight into not only a fun-filled adventurous novel, but also one in which Milo, the hero, even has a quest or mission to fulfill?

JUSTER: God, I don't know whether I can really answer that. Some of the questions you're asking sort of imply that that's what I was trying to do. And I was really messing around with what I thought was a little story. And when I started writing it, it was as a recreation from something else I had been doing. And it just grew. And I also wrote different sections - I didn't write it totally sequentially. I'd write a piece. And another piece. And I just sort of set them aside. And after a while I began setting things together. So there's not a lot of sort of predetermined idea of what's gonna happen.

And when I'm writing, I write a lot anyway. I might write pages and pages of conversation between characters that don't necessarily end up in the book, or in the story I'm working on, because they're simply my way of getting to know the characters. And one of the nice things that happens -- it doesn't happen that often when you're writing, is that when you're writing a scene, say between characters, where you can get the feeling that all you're doing is eavesdropping, and the characters are doing the talking. And you're just jutting it down as fast as you can -- you're not making up dialog. The characters have a life and they're talking, and you're just recording. Now, again, that doesn't happen that often. But when it does it's a marvelous moment -- when you'll be able to do that.

And so when I started this book I had no outline. I had no idea what was happening. As I said, I didn't know it was gonna be a book. I thought it was just a little episode or a story. When it got going it began to sort of piece itself together. The whole thing happened in a very strange way. I would not recommend it as a way to write a book for anybody.

RES: It's said that writing is rewriting. Did you have to rewrite The Phantom Tollbooth many times?

JUSTER: I write in a very laborious kind of a way. I write and rewrite. And rewrite. And rewrite. Well, the thing of course is if you're doing it well, when you finish your 30th rewrite, or something, it should sound like you've just written it completely, freshly once. Because sometimes what happens when you write and rewrite and rewrite, is you suck the life out of something. It's difficult. But I find that I do that because it's amazing -- the rhythm of the book, or what I call the music of the book -- how you read it. How you're carried along by the words and the subject -- is as important as the meaning. In fact, you can't have one without the other.

It's one of the reasons that kids go with any book, because they can move through it in a way that's both acceptable and pleasurable for them. Not a conscious thing, I don't think. Certainly not with the kids. But I think it's very important. I mean, I'll work over a sentence or a paragraph where it's sometimes a matter of a word, a comma, in a certain place that will be very subtle in its difference. But when I get it to the point where I can say, "Yes that's it. That's the way it has to be," then I know I'm okay.

RES: A book as clever as yours can be categorized in the same class as Dr. Seuss' and Shel Silverstein's verses, in that they're all incomparably impossible to emulate. Could such works conceivably defeat aspiring childrens' book authors who don't think they can ever write anything even remotely similar? Or should they even try to?

JUSTER: That's a big question. I don't think you try to write a style or model it on something. There's no way you should do that. You have to start doing it just as you feel it, and see it, and hear it. The only other thing which I think is important is: Don't write a book or start a book with the expectation of communicating a message in a very important way. I mean [with a message] underlying it, of course. That's one criticism I would make at a couple of points where I say to myself it's just too didactic. When you start to see it, or feel it, then you know you've overplayed your hand a little bit.

But I know that there are many books for children now -- the reason for their being is to deal with a problem, you know, whether it's adolescence drug abuse, or something. And in many cases they fail because they're so preoccupied with the idea of communicating a message that the situation and the characters become fairly wooden within them. Which is not to say that you shouldn't write a book in which these things exist, and are part of the story. But I don't think you start with the idea that that's the most important thing. The most important things are the characters and situations -- what happens. I don't know whether that makes sense or not.

RES: Yes it does. Of course it does. It also answers the question I was going to ask about message books.

JUSTER: I don't want to be misunderstood. I'm not saying that writing books about these difficult subjects is wrong. Or it's not the way to do things. But I think if you write a book, the message, or whatever it is that derives from the truth of the characters and the situations you set up -- you don't start with the idea of this is the way it's going to come out -- this is the way I want someone to think about it. And then make all the characters and situations conform to that. There are many surprises in books. And I think almost any author you speak to will tell you that there are times when you start writing a story or book which you think is going one way, and the characters take off and go somewhere else.

RES: You also said, in the interview, that writing The Phantom Tollbooth was a lot of fun for you. That writing certain portions of it were even like playing a game. Is there any correlation between an author enjoying the writing of a childrens' book, and kids' loving the book he/she's written? Or can it possibly be said that kids will enjoy, or be engaged with a book to the same degree that a writer enjoyed writing it? And that the reverse is also true -- if writing the book was sheer torture kids will hate reading it too?

JUSTER: I don't think you can make that connection as literally as you're posing the question. It's interesting because you may have misinterpreted, but I find that writing is a very bleak, and lonely, and stressful, and often unhappy occupation. And I find this is not only with me when I talk to other writers. First of all you eat it. You sleep it. You can't get it out of your head. You wake up in the morning constantly with this idea of staring at this blank page -- you've lost it -- you're never going to get what you know you feel.

What's most interesting is that, say that goes on for several months while you're working. That several months' period of time can be an absolute misery. At the same time, when you finish and you look back on that time it's somehow a very satisfactory -- if you can use the word happy, time. Because what has happened, of course, is that you have gotten into a situation where you are so much at risk, and so much testing yourself, and this thing means so much to you, like anything else you do, you're constantly on tenterhooks with this thing. So, I don't write easily. I know writers. I have friends who write fairly easily. I don't. And I don't view writing as the simplest thing -- a pleasurable experience. At the same time the whole process is one that provides a great deal of fulfillment and satisfaction. Now again, this might not make any sense.

RES: What I was referring to in the above question was your chapter about Milo's dinner with the city's dignitaries, at which I think he had to "eat his words." Writing it, I believe you said, was as much fun as playing a game. (That's not a verbatim quote).

JUSTER: Well, one of the things about my life is that I play games constantly. Not formal games. But little things throughout the day that help me deal with some of the more humdrum or trivial tasks of life. It's just a very personal way of dealing with things. So sometimes, yes, when you're working on something you have that aspect. I can remember there were times when I worked on the book where I could stop for a moment at certain scenes and say, "My God, I'm writing a monster," at this point. Because there was that kind of insanity that ran through the scene, and the characters and the dialog that ultimately produced its own kind of wisdom, if you know what I mean. And that's what I love.

I love Marx brothers movies. I still do. I still watch them when they're on or I'll rent one, or something. Because what they do, which is what this book tries to do -- they turn the world absolutely upside down, and look at things from a totally different way. And I guess that if there's any message in the book at all, and this is after the fact, I didn't start with this idea, it is that that's what you really have to do. You have to constantly look at things as if you've never seen them before. Or look at them in a way that nobody has ever seen them before. Or turn them over and look at the other side of everything.